When communities are asked to contribute their time or money to shared goals—like running a school meal program—the success of these efforts often depends on how people respond to one another’s choices. If most people give more time and effort when others do, cooperation can spread. But if people hold back when they see others contributing, cooperative efforts may falter. In economics, this concept is called “conditional cooperation,” and it has been almost exclusively studied using laboratory games in wealthy countries, often with university students—far from the realities of rural life in places where public goods depend heavily on donations and volunteering.

Our recent IFPRI Discussion Paper fills this gap: We implemented a lab-in-the-field experiment assessing conditional cooperation for a new school meals program implemented by World Vision in Nampula and Zambezia provinces in rural Mozambique. Communities participating in the program are asked to help sustain it by donating small amounts of money or volunteering their time to cook and serve food. We asked households to describe their willingness to contribute depending on how many other households also decided to chip in and contribute to the program.

What emerged was surprising: Patterns of community cooperation in rural Mozambique differed markedly from those in studies in high-income, laboratory settings—challenging standard expectations about cooperation behavior and also suggesting that people’s willingness to contribute to community programs may be shaped by factors that typical models overlook, such as social cohesion.

How can we measure this?

To understand “conditional cooperation” in a real-world low-income setting, we worked with 1,248 households across 156 villages in the two provinces. In each community, we interviewed eight households, asking how much they would give to the school meals program if no other household donated, one other household donated, two other households donated, etc., all the way to all seven other households donating. They were also asked how many shifts they would volunteer to cook or clean, again depending on others’ participation (again, from zero to seven other households).

To enable households to make meaningful choices, we offered households a small amount of money (about the price of a meal) to either donate or keep for themselves and explained that we were collecting a list of interested volunteers for World Vision. We then explained that, after surveying all households in the community, we would carry out their responses (donating to the school lunch program or adding their names to volunteer lists) based on the number of other households that contributed. Thus, these decisions had real-world consequences for participants and represented actual behavior.

For comparison, we also asked how much money or time they would contribute if they did not know how many other households were contributing. Over 95% were willing to make some donation of money or time, indicating that contributing to community projects is a common behavior in this setting, overall.

How did people behave?

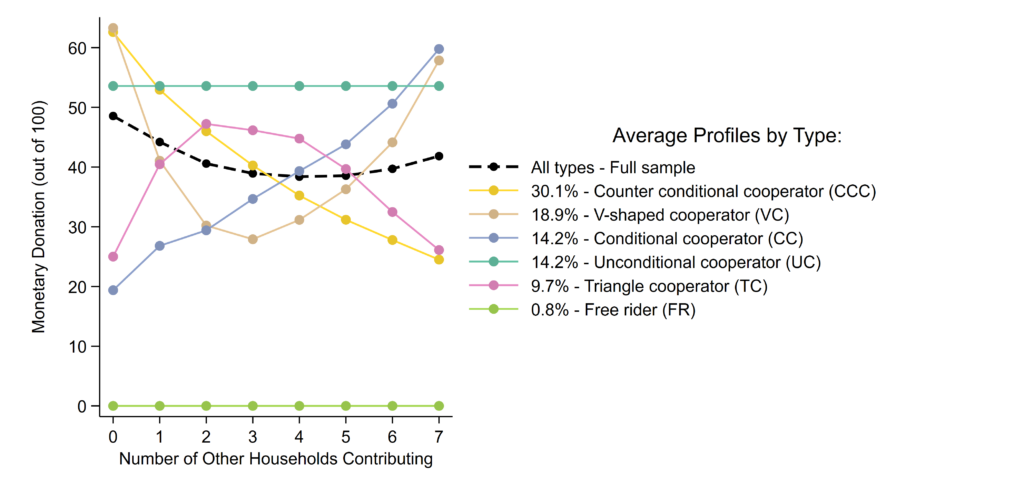

First, the responses revealed striking differences from the patterns found in other studies (Figure 1). More than half of respondents did not fit into any of the standard categories that past researchers have used to describe cooperative behavior. Namely, only a small share of participants increased their contributions as others did—the “conditional cooperation” (CC) type that is the most common behavior identified in studies that take place in high-income laboratory settings.

Figure 1: Average contribution type if other households contribute – donations

Instead, the most common pattern was the opposite: Many people offered less when others gave more, which is called “counter conditional cooperation” (CCC). Another contribution pattern formed a V-shape—participants gave a lot when very few or many households contributed, but dipped in the middle. These two types of behavior, largely absent from previous research, together accounted for more than half of all participants. One possible explanation is that individuals’ preferences are different in a real-world, low-income context where “others” are not simply strangers in the same experiment, but rather neighbors with shared community values and a long history of working together to address public needs.

Second, this general pattern held true for donations of both money and time (Figure 2). This consistency suggests that the way people respond to others’ efforts reflects deeper social norms or perceptions about fairness and responsibility, not just the type of contribution being asked.

Figure 2: Average contribution type if other households contribute – volunteering

Third, we found that social cohesion mattered. In some communities, where interviews showed people trusted one another and believed that resources were managed fairly, counter-cooperative and free-riding behavior was less common. Households in these settings were more likely to give steadily, regardless of what others did, or even increase their contributions as others did. This points to the importance of trust and shared norms in sustaining collective programs.

Implications for community programs

The findings make clear that community programs that depend on voluntary contributions must recognize that cooperation is complicated: people respond to what they expect others will do, and these expectations may depend on perceptions of social cohesion. We make the following policy recommendations:

- Integrate behavioral insights into community program design. Recognizing that people’s responses depend on perceived fairness and others’ behavior can lead to more effective local governance. Embedding behavioral monitoring in program management will help implementers adjust strategies in real time, helping to ensure that cooperation grows rather than declines. For example, in our setting, implementers should not emphasize how many others are contributing if they want more households to make contributions.

- Invest in social cohesion before seeking to rely on community contributions. While not explicitly tested for, our results suggest that building trust among community members and strengthening fair, transparent leadership can shift contribution patterns from counter-cooperative to cooperative.

Programs that rely on voluntary effort cannot assume that goodwill alone will sustain them. Taking these steps can transform fragile participation into collective commitment—an essential condition for achieving lasting progress toward food security and community-driven development.

James Allen IV is an Associate Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Gender, and Inclusion (PGI) Unit; Naureen Karachiwalla is a PGI Research Fellow; Deboleena Rakshit is a PGI Research Analyst. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.

We acknowledge funding from World Vision. This work was also undertaken as part of the CGIAR Science Program on Policy Innovations. We would like to thank all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. Finally, we thank the participants in this survey for their time.

During the preparation of this blog post, the authors used ChatGPT-4 to obtain suggestions on how to improve readability and brevity. After using this service, the authors carefully reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Reference:

Allen IV, James; Karachiwalla, Naureen; and Rakshit, Deboleena. 2025. Are poor people conditionally cooperative? Contrasting evidence from a field-adapted contributions game. IFPRI Discussion Paper 2364. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/176850