Reprinted with permission from VoxDev.

Formally including Ugandan women in commercial agriculture—through contract ownership or behavior-change interventions—can increase women’s empowerment without reducing productivity, and with positive spillovers for household welfare and gender relations.

Estimates suggest that there are 475 million smallholder farms in low- and middle-income countries, including 43 million in sub-Saharan Africa (Lowder et al. 2016, FAO 2017). For these farmers, engaging in commercial value chains can have positive impacts on economic outcomes such as income, employment, and farm productivity, as well as on other outcomes like consumption and nutrition (Ogutu et al. 2020, Saha et al. 2021). However, pivoting from subsistence towards commercial production involves risks in terms of fallback food security; it may also shift control of production and resources within a household.

Researchers have documented that an individual’s empowerment, defined as the ability to make decisions about one’s life and act upon them, is strongly linked to access to resources (Kabeer 1999, Ashraf et al. 2010, Doss 2013, Ambler 2016). In many smallholder households, women grow kitchen gardens and often larger plots to ensure subsistence. This gives women some measure of control over an important household resource. When land is shifted to commercial production, resource control may also change, skewing the balance of power towards men, who often already have a resource advantage. As such, though agricultural commercialization may raise incomes, it may not have even impacts across men and women absent specific policy interventions (DeWalt 1993, Hill and Vigneri 20091).

Increasing the inclusion of women in commercial value chains may help households realize the benefits of commercial agriculture without significant shifts in resource control. However, this policy approach also has risks. If a household has already established commercial engagement, they may be resistant to changing their arrangements, as transferring (partial) control of commercial plots to women would increase women’s access to resources at the expense of men. It is not clear whether this would be achievable, and if so, what the aggregate welfare implications would be. Further, given the well-documented gender gaps in agricultural productivity, such transfers may also risk reducing yields (Quisumbing 1996, Udry 1996, Goldstein and Udry 2008).

Studying gender inclusivity in commercial agriculture

To understand whether commercialization can be used as a tool to promote women’s empowerment, we created the Farm and Family Balance project (Ambler, Jones, and O’Sullivan 2026). Our goal was to understand women’s participation in agricultural commercialization in the Lake Victoria region of Uganda through a comparison of two different interventions. We partnered with a large sugarcane processor who buys cane from smallholder farmers. In the first intervention, households that generally contracted their sugarcane only in the name of the husband, were encouraged to instead contract a portion of that cane in the name of the wife. The contract holder may request inputs on credit and cash advances on cane sales and receives final payments into a personal bank account after cane delivery. Our goal was to understand whether giving women control of the cane contract and access to the income from cane sales would affect their empowerment and consequently measures of well-being within their households.

We additionally implemented a second intervention in which households were invited to a three-day, participatory couples’ workshop designed to increase household cooperation, with a focus on economic activities. The goal of these workshops was to allow the comparison of a behavior-change intervention with the economic approach taken with the contract intervention.

More than 2,300 couples were enrolled in our study and were randomly divided into four groups: a control group, a group that received the contract intervention only, a group that received the workshop intervention only, and a group that received both. Take-up of the interventions was high. More than 70% of households in both groups that were offered contracts decided to contract one or more sugarcane blocks in the wife’s name. Approximately 75% of couples invited to the workshops had both spouses attend at least two of the three days. We returned more than a year later to interview the couples and measure impacts of the interventions.

Women’s power, productivity, and household welfare

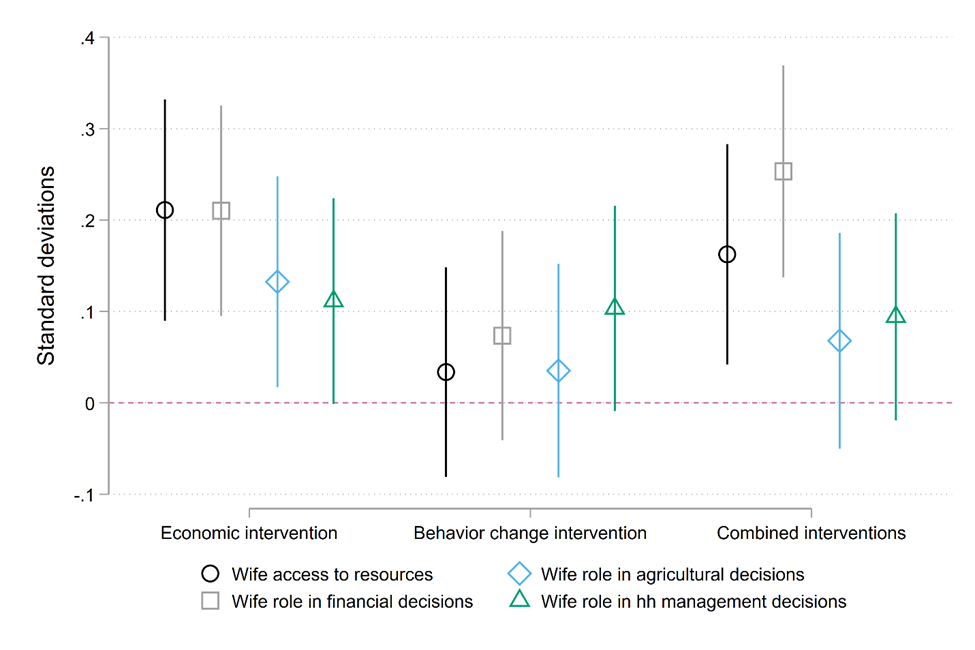

We found that both interventions did in fact empower women, but in different ways. Making a woman the contract holder gave her rights to the proceeds on paper, which we found also translated into real changes in her involvement in sugarcane marketing, including her knowledge of sugarcane production and reported participation in both production and sales. We also found that this did change her control of income and agency within her household, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Impact of project interventions

Women offered the contract intervention had higher levels of access to resources, and an increased role in financial, agricultural, and household management decisions. Conversely, for women receiving the workshop only, we note increases only in measures of self-concept.

Despite previous evidence that agricultural plots controlled by women can be less productive, we found no evidence of this for sugarcane blocks contracted to women. There were also no changes in production for sugar or other crops. These are encouraging results suggesting that female management of agricultural production will not always lead to decreased productivity.

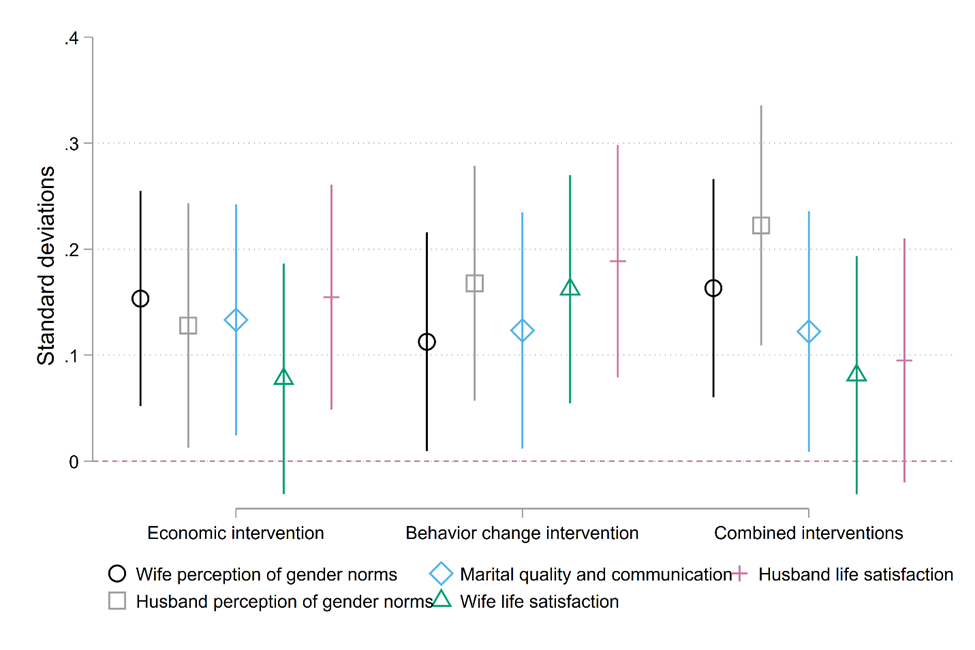

We also document interesting impacts of thecontract offer on men, as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Impact of project interventions

The program improved perceptions of gender norms held by women and men, as well as reported marital quality, communication, and men’s life satisfaction. While the workshops did not change most measures of agency, they did result in a similar pattern of improvements in these measures. Thus, the behavior change intervention was successful in changing some aspects of how households functioned, but the shift in financial control provided by the contract intervention was needed to change access to resources and household decision-making.

Policy implications for women’s empowerment

Our results suggest that increased women’s empowerment does not need to be a ‘zero-sum’ goal. While many stakeholders were concerned that men would reject registering contracts with women, in reality take-up was high. Many men welcomed the opportunity to formally include women in commercial activities, and both spouses appear to be better off. While the research team facilitated the implementation of block registrations, the registration of contracts with women was a light-touch intervention that could be inexpensively adapted and scaled by the private sector, making it an attractive and economically feasible policy option for increasing women’s empowerment. Our research did not address business impacts on the company, but incorporating such a strategy into its business model should only grow the base of qualified outgrowers. Moreover, contract farming is a setting that lends itself well to such a design, but this concept can also be adapted to other types of contracts. For example, targeting input financing agreements for livestock or crops to women could improve their control over the outputs, especially if repayment is linked to product sale. Promoting the adoption of such ideas in the private sector has the potential to sustainably increase women’s empowerment and change gender norms at low cost.

Kate Ambler is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions Unit; Kelly Jones is an Associate Professor of Economics at American University, Washington, D.C.; Michael O’Sullivan is Lead Economist and Head of the World Bank’s Africa Gender Innovation Lab. This post was first published on VoxDev. Opinions are the authors’.

This work was funded by the World Bank Umbrella Facility for Gender Equality, the Africa Gender Innovation Lab, the CGIAR Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets, and the IFPRI Strategic Innovation Fund.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out our VoxDevLits on Female Labour Force Participation and Agricultural Technology in Africa. The authors have made slides available here.

1. Hill, R V, and M Vigneri (2009), “Mainstreaming gender sensitivity in cash crop market supply chains,” Unpublished manuscript.