Community health workers (CHWs) increasingly play a central role in delivering essential primary health services in low-income settings. By providing doorstep services such as diagnosis and treatment of childhood illnesses, health promotion, and referrals, CHWs are widely viewed as a promising and cost-effective way to extend health systems to underserved populations (Bhandari et al., 2012; Gaye et al., 2020; Whidden et al., 2023). Yet important questions remain about how these programs should be structured to achieve the greatest health gains where resources are severely limited.

One fundamental question concerns the number of people that CHW should be responsible for—that is, their caseload. In practice, CHW caseloads vary widely, both across countries and within them. Program guidelines often specify target population-to-CHW ratios, but these benchmarks are typically based on planning norms rather than empirical evidence. In fragile and conflict-affected settings, where health systems are strained and resources are limited, getting this ratio right is especially important. If caseloads are too large, CHWs may be unable to provide frequent or high-quality services. If they are too small, scarce resources may be used inefficiently.

This blog post summarizes new experimental evidence from a large cluster-randomized trial in Mali that directly addresses this issue: how do CHW caseloads influence children’s health, and how do different approaches—home health visits vs. CHWs stationed at clinics or other fixed sites—affect those results? In short, I find that CHW fixed-site care becomes less effective when it is assigned a relatively high caseload—but that this is not the case of CHW proactive home visits, suggesting that home visits offer the most added benefit in places where the population-to-CHW ratio is necessarily high.

Background: A large-scale randomized trial of CHW proactive home visits

The analysis draws on rich data from the Proactive Community Case Management (ProCCM) trial implemented by U.S. non-profit Muso, which tested whether proactive home visits by professional CHWs improved child survival relative to fixed-site CHW care (Liu et al., 2024). The trial occurred in the rural Bankass district of Mali between February 2017 and January 2020 as a complement to Muso’s earlier work in the peri-urban suburbs of Mali’s capital Bamako (Johnson et al., 2018). Despite global declines in under-5 mortality, Mali continues to experience an alarming 91 under-5 deaths per 1,000 live births (UNICEF) amid recurrent insecurity, population displacement, and weak health infrastructure.

While CHWs usually provide care from fixed community sites, the hypothesis was that proactive home visits would reduce delays in care-seeking and thus improve health access for sick and otherwise vulnerable children.

To test this, the trial randomized 137 village-clusters to receive either proactive CHW home visits or fixed-site CHW service delivery. In assigning CHWs to communities, Muso targeted a ratio of roughly 700 people per CHW and would assign multiple CHWs to work separately in more populated communities if necessary. Importantly, both arms received the same clinical package: salaried and professionally trained CHWs, monthly supervision, standardized treatment protocols, removal of user fees, and major upgrades to primary health centers. The only difference was how care reached households—through routine home visits or via fixed community sites.

Household survey data were collected at baseline and at 12, 24, and 36 months, covering nearly all households in the study area. These surveys recorded complete birth histories, allowing the construction of monthly mortality risk for children under 5. Across the study period, more than 31,000 children contributed over 52,000 person-years of observation, yielding more than 630,000 child-months for analysis.

In the end, the trial detected no average difference between delivery models but did observe that mortality declined dramatically across all study communities during the intervention, likely due to all villages receiving new professional CHWs, health center upgrades, and cost reductions for medical care (Liu et al., 2024). The evaluation found no differential impacts by cluster population, distance to health facility, or household wealth. However, it did not test for heterogeneity by CHW caseload.

Methods: measuring and analyzing CHW caseloads

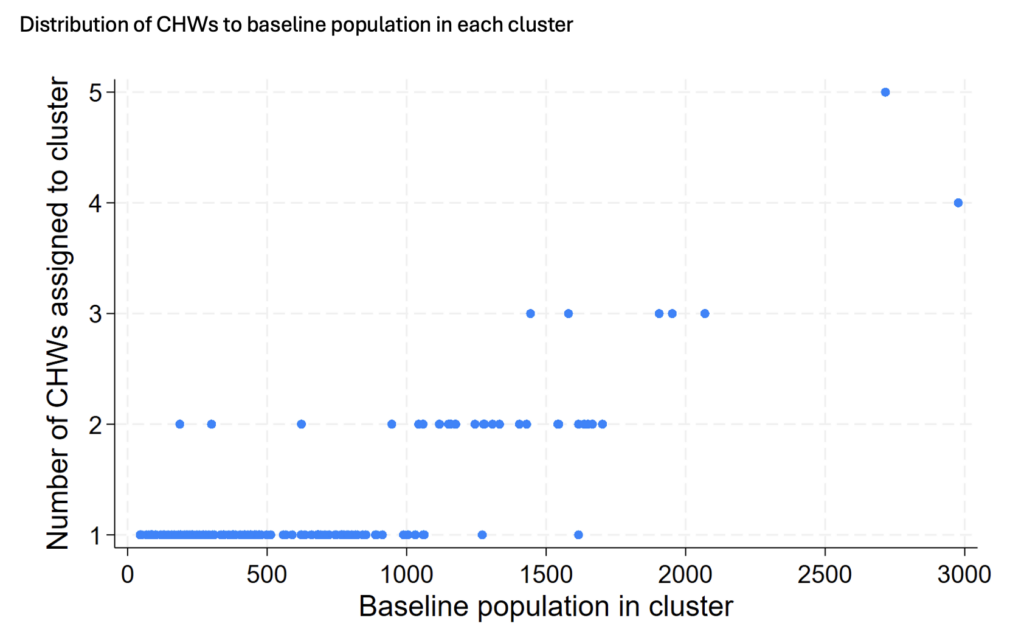

Since CHWs were expected to serve the entire population, we require an accurate measure of each village-cluster’s population prior to the intervention to measure each CHW’s caseload. The ProCCM trial’s baseline survey captured approximately 98% of households in the study area, effectively constituting a census, allowing for cluster populations to be calculated directly from household rosters. However, when Muso initially allocated CHWs across communities, it did not yet have access to these baseline population counts and instead relied on pre-baseline estimates that differed from actual population levels. As a result, the relationship between true baseline population and CHW assignment partially overlaps (Figure 1), generating useful variation in population-to-CHW ratios separate from baseline population.

Figure 1

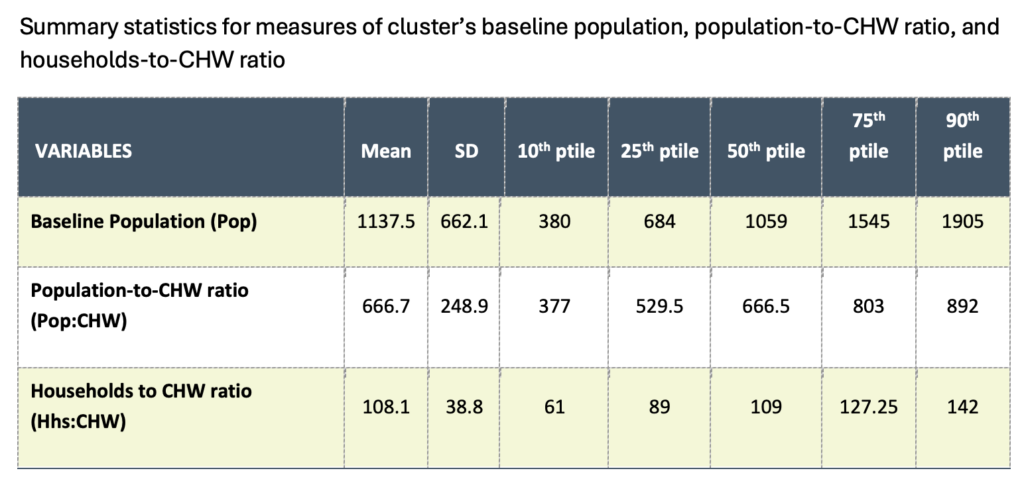

Table 1 shows substantial variation in caseloads. Cluster populations averaged 1,137 people but ranged widely from only 380 people at the 10th percentile to 1,905 at the 90th percentile, but larger clusters often received multiple CHWs. Thus, cluster population-to-CHW ratios only averaged 667 people per CHW, ranging from 377 people per CHW at the 10th percentile to 892 people per CHW at the 90th percentile. This reveals that some CHW had caseloads more than 2.5 times larger than other CHWs.

Table 1

To estimate how impacts vary by caseload, the analysis updates the regression models of the original trial evaluation (Liu et al., 2024)—maintaining the primary outcome of all-cause under-5 mortality and controls for child age, sex, and distance to the nearest primary health center—to test whether treatment effects differ above and below multiple cutoffs of population-to-CHW ratios.

Findings: Large caseloads diminish impact of fixed-site CHWs

The results reveal a clear and consistent pattern as caseloads rise for fixed-site CHWs: in clusters where a single CHW served approximately 900 people—around the 90th percentile of the population-to-CHW ratio—children in control clusters with fixed-site care faced significantly higher mortality risk relative to children living in control clusters below the cutoff. By itself, this suggests that CHW fixed-site care becomes less effective when it is assigned a relatively high caseload. This may be because fixed-site CHWs are harder for caregivers to find or identify or, once they are found, they are too busy to adequately serve everyone.

However, in treated clusters where a CHW made proactive home health visits, under-5 mortality did not rise when caseloads reached 900. This suggests that proactive home visits may work better as a CHW health service delivery model when CHWs face larger caseloads that would otherwise strain their efficacy. A similar pattern emerges when caseloads are defined by households rather than population. At roughly 140 households per CHW, children in control clusters again experienced significantly higher mortality risk, while children in treatment clusters did not.

Yet, the analysis finds no comparable heterogeneity when comparing treatment effects by baseline population alone, not considering levels of CHW staffing. Large clusters do not systematically benefit more from proactive home visits—unless CHW coverage is thin. This distinction strengthens the interpretation that caseload pressure—not population size per se—drives the differential impacts, producing the clear benefit from home visits in such circumstances.

Implications for CHW program design

These findings have direct implications for CHW program design in fragile and conflict-affected settings where health systems must make strategic staffing decisions under serious funding constraints and have limited evidence on optimal CHW deployment.

The results suggest that proactive outreach may be particularly valuable in settings where CHWs face heavy caseloads at fixed sites, highlighting the need for staffing models that explicitly account for variation in population-to-provider ratios. More broadly, this analysis contributes evidence that CHW program effectiveness depends not only on what services are delivered, but how and under what staffing conditions they are delivered.

By documenting differential impacts across CHW density thresholds, this analysis provides actionable insights for Ministries of Health, implementing partners, and donors seeking to maximize the benefits of CHW investments to health and survival. In contexts like rural Mali—where insecurity and displacement create persistent barriers to care—targeted deployment of proactive home visits in high-ratio areas may enhance resilience, improve timely access to treatment, and strengthen primary health care delivery. Future work incorporating CHW performance and visit-frequency data will help clarify mechanisms and refine guidance for optimal CHW-to-population ratios in similarly constrained health systems.

James Allen IV is an Associate Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Gender and Inclusion Unit. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the author’s.

This work was supported by the donors who fund the CGIAR Science Program on Food Frontiers and Security through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund. I also thank Emily Treleaven and Arsène Sandie for the feedback and efforts to set up a data use agreement with IFPRI. See project note for full list of acknowledgements. The author used a generative AI tool as an editorial aid while drafting the blog post, primarily to improve clarity, coherence, and brevity of the written text. The AI was not used to generate original research content. All content was carefully reviewed and revised by the author, who retains full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the publication.

Reference:

Allen IV, James. 2025. Community health worker caseloads, home visits, and child survival: Experimental evidence of heterogenous effects from Mali. FCA Brief. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/178959.